Describes how to code the user interface of the Address Book Example. This first part covers the design of the basic graphical user interface (GUI) for our address book application.

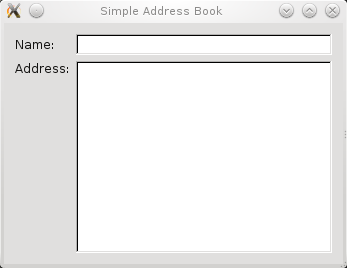

The first step in creating a GUI program is to design the user interface. Here the our goal is to set up the labels and input fields to implement a basic address book. The figure below is a screenshot of the expected output.

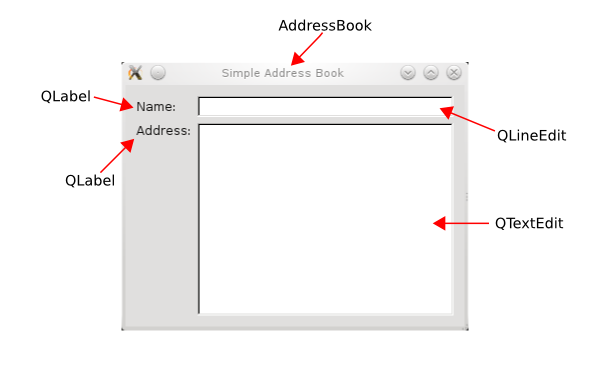

We require two QLabel objects, nameLabel and addressLabel, as well as two input fields, a QLineEdit object, nameLine, and

a QTextEdit object, addressText, to enable the user to enter a contact's name and address. The widgets used and their positions are shown in the figure below.

There are three files used to implement this address book:

addressbook.h - the definition file for the AddressBook class,addressbook.cpp - the implementation file for the AddressBook class, andmain.cpp - the file containing a main() function, with an instance of AddressBook.When writing Qt programs, we usually subclass Qt objects to add functionality. This is one of the essential concepts behind creating custom widgets or collections of standard widgets. Subclassing to extend or change the behavior of a widget has the following advantages:

Since Qt does not provide a specific address book widget, we subclass a standard Qt widget class and add features to it. The AddressBook class we create in this tutorial can be reused in situations where a basic

address book widget is needed.

The tutorials/addressbook/part1/addressbook.h file is used to define the AddressBook class.

We start by defining AddressBook as a QWidget subclass and declaring a constructor. We also use the Q_OBJECT macro to indicate that the

class uses internationalization and Qt's signals and slots features, even if we do not use all of these features at this stage.

class AddressBook : public QWidget { Q_OBJECT public: AddressBook(QWidget *parent = nullptr); private: QLineEdit *nameLine; QTextEdit *addressText; };

The class holds declarations of nameLine and addressText, the private instances of QLineEdit and QTextEdit mentioned earlier. The

data stored in nameLine and addressText will be needed for many of the address book functions.

We don't include declarations of the QLabel objects we will use because we will not need to reference them once they have been created. The way Qt tracks the ownership of objects is explained in the next section.

The Q_OBJECT macro itself implements some of the more advanced features of Qt. For now, it is useful to think of the Q_OBJECT macro as a shortcut which allows us to use the tr() and connect() functions.

We have now completed the addressbook.h file and we move on to implement the corresponding addressbook.cpp file.

The constructor of AddressBook accepts a QWidget parameter, parent. By convention, we pass this parameter to the base class's constructor. This concept of ownership, where a

parent can have one or more children, is useful for grouping widgets in Qt. For example, if you delete a parent, all of its children will be deleted as well.

AddressBook::AddressBook(QWidget *parent) : QWidget(parent) { QLabel *nameLabel = new QLabel(tr("Name:")); nameLine = new QLineEdit; QLabel *addressLabel = new QLabel(tr("Address:")); addressText = new QTextEdit;

In this constructor, the QLabel objects nameLabel and addressLabel are instantiated, as well as nameLine and addressText. The tr() function returns a translated version of the string, if there is one available. Otherwise it returns the string itself. This function marks its QString parameter as

one that should be translated into other languages. It should be used wherever a translatable string appears.

When programming with Qt, it is useful to know how layouts work. Qt provides three main layout classes: QHBoxLayout, QVBoxLayout and QGridLayout to handle the positioning of widgets.

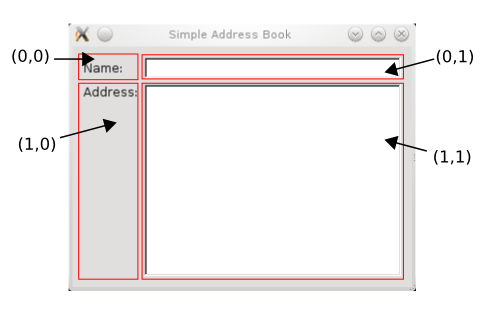

We use a QGridLayout to position our labels and input fields in a structured manner. QGridLayout divides the available space into a grid and places widgets in the cells we specify with row and column numbers. The diagram above shows the layout cells and the position of our widgets, and we specify this arrangement using the following code:

QGridLayout *mainLayout = new QGridLayout; mainLayout->addWidget(nameLabel, 0, 0); mainLayout->addWidget(nameLine, 0, 1); mainLayout->addWidget(addressLabel, 1, 0, Qt::AlignTop); mainLayout->addWidget(addressText, 1, 1);

Notice that addressLabel is positioned using Qt::AlignTop as an additional argument. This is to make sure it is not vertically centered in cell (1,0). For a basic

overview on Qt Layouts, refer to the Layout Management documentation.

In order to install the layout object onto the widget, we have to invoke the widget's setLayout() function:

setLayout(mainLayout);

setWindowTitle(tr("Simple Address Book"));

}

Lastly, we set the widget's title to "Simple Address Book".

A separate file, main.cpp, is used for the main() function. Within this function, we instantiate a QApplication object, app. QApplication is responsible for various application-wide resources, such as the default font and cursor, and for running an event loop. Hence, there is always one QApplication object in every GUI application using Qt.

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { QApplication app(argc, argv); AddressBook addressBook; addressBook.show(); return app.exec(); }

We construct a new AddressBook widget on the stack and invoke its show() function to display it. However, the widget will not be shown until the application's event loop is

started. We start the event loop by calling the application's exec() function; the result returned by this function is used as the return value from the main() function. At

this point, it becomes apparent why we instantiated AddressBook on the stack: It will now go out of scope. Therefore, AddressBook and all its child widgets will be deleted, thus preventing memory

leaks.