When you develop applications for several different mobile device platforms, you face the following challenges:

Qt Quick enables you to develop applications that can run on different types of devices, such as tablets and handsets. In particular, they can cope with different screen configurations. However, there is always a certain amount of fixing and polishing needed to create an optimal user experience for each target platform.

You need to consider scalability when:

To implement scalable applications using Qt Quick:

Consider the following patterns when designing your application:

Qt Quick Controls provide a set of UI controls to create user interfaces in Qt Quick. Typically, you declare an ApplicationWindow control as the root item of your application. The ApplicationWindow adds convenience for positioning other controls, such as MenuBar, ToolBar, and StatusBar in a platform independent manner. The ApplicationWindow uses the size constraints of the content items as input when calculating the effective size constraints of the actual window.

In addition to controls that define standard parts of application windows, controls are provided for creating views and menus, as well as presenting or receiving input from users. You can use Qt Quick Controls Styles to apply custom styling to the predefined controls.

Qt Quick Controls, such as the ToolBar, do not provide a layout of their own, but require you to position their contents. For this, you can use Qt Quick Layouts.

Qt Quick Layouts provide ways of laying out screen controls in a row, column, or grid, using the RowLayout, ColumnLayout, and GridLayout QML types. The properties for these QML types hold their layout direction and spacing between the cells.

You can use the Qt Quick Layouts QML types to attach additional properties to the items pushed to the layouts. For example, you can specify minimum, maximum, and preferred values for item height, width, and size.

The layouts ensure that your UIs are scaled properly when windows and screens are resized and always use the maximum amount of space available.

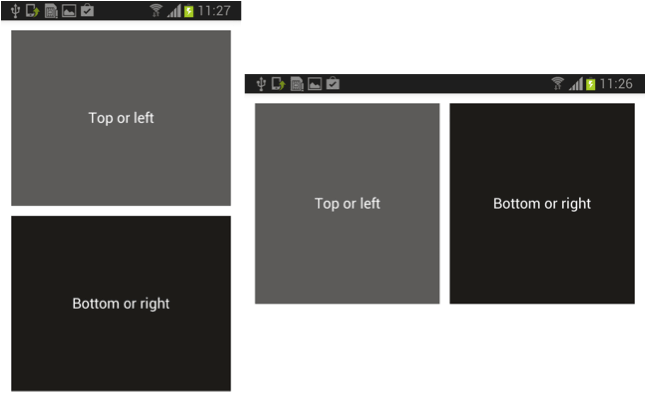

A specific use case for the GridLayout type is to use it as a row or a column depending on the screen orientation.

The following code snippet uses the flow property to set the flow of the grid from left to right (as a row) when the screen width is greater than the screen height and from top to bottom (as a

column) otherwise:

ApplicationWindow {

id: root

visible: true

width: 480

height: 620

GridLayout {

anchors.fill: parent

anchors.margins: 20

rowSpacing: 20

columnSpacing: 20

flow: width > height ? GridLayout.LeftToRight : GridLayout.TopToBottom

Rectangle {

Layout.fillWidth: true

Layout.fillHeight: true

color: "#5d5b59"

Label {

anchors.centerIn: parent

text: "Top or left"

color: "white"

}

}

Rectangle {

Layout.fillWidth: true

Layout.fillHeight: true

color: "#1e1b18"

Label {

anchors.centerIn: parent

text: "Bottom or right"

color: "white"

}

}

}

}

Constantly resizing and recalculating screens comes with a performance cost. Mobile and embedded devices might not have the power required to recalculate the size and position of animated objects for every frame, for example. If you run into performance problems when using layouts, consider using some other methods, such as bindings, instead.

Here are some things not to do with layouts:

If Qt Quick Layouts do not fit your needs, you can fall back to using property binding. Binding enables objects to automatically update their properties in response to changing attributes in other objects or the occurrence of some external event.

When an object's property is assigned a value, it can either be assigned a static value, or bound to a JavaScript expression. In the former case, the property's value will not change unless a new value is assigned to the property. In the latter case, a property binding is created and the property's value is automatically updated by the QML engine whenever the value of the evaluated expression changes.

This type of positioning is the most highly dynamic. However, constantly evaluating JavaScript expressions comes with a performance cost.

You can use bindings to handle low and high pixel density on platforms that do not have automatic support for it (like Android, macOS and iOS do). The following code snippet uses the Screen.pixelDensity attached property to specify different images to display on screens with low, high, or normal pixel density:

Image {

source: {

if (Screen.pixelDensity < 40)

"image_low_dpi.png"

else if (Screen.pixelDensity > 300)

"image_high_dpi.png"

else

"image.png"

}

}

On Android, macOS and iOS, you can provide alternative resources with higher resolutions by using the corresponding identifier (e.g. @2x, @3x, or @4x) for icons and images, and place them in the resource file. The version that matches the pixel density of the screen is automatically selected for use.

For example, the following code snippet will try to load artwork@2x.png on Retina displays:

Image {

source: "artwork.png"

}

Some QML types, such as Image, BorderImage, and Text, are automatically

scaled according to the properties specified for them. If the width and height of an Image are not specified, it automatically uses the size of the source image, specified using the source property.

By default, specifying the width and height causes the image to be scaled to that size. This behavior can be changed by setting the fillMode property, allowing the image to be stretched and tiled

instead. However, the original image size might appear too small on high DPI displays.

A BorderImage is used to create borders out of images by scaling or tiling parts of each image. It breaks a source image into 9 regions that are scaled or tiled according to property values. However, the corners are not scaled at all, which can make the results less than optimal on high DPI displays.

A Text QML type attempts to determine how much room is needed and set the width and height properties accordingly, unless they

are explicitly set. The fontPointSize property sets the point size in a device-independent manner. However, specifying fonts in points and other sizes in pixels causes problems, because points are

independent of the display density. A frame around a string that looks correct on low DPI displays is likely to become too small on high DPI displays, causing the text to be clipped.

The level of high DPI support and the techniques used by the supported platforms varies from platform to platform. The following sections describe different approaches to scaling screen contents on high DPI displays.

For more information about high DPI support in Qt and the supported platforms, see High DPI.

On macOS and iOS, applications use high DPI scaling that is an alternative to the traditional DPI scaling. In the traditional approach, the application is presented with an DPI value used to multiply font sizes, layouts, and so on. In the new approach, the operating system provides Qt with a scaling ratio that is used to scale graphics output: allocate larger buffers and set a scaling transform.

The advantage of this approach is that vector graphics and fonts scale automatically and existing applications tend to work unmodified. For raster content, high-resolution alternative resources are needed, however.

Scaling is implemented for the QtQuick and QtWidgets stacks, as well as general support in QtGui and the Cocoa platform plugin.

The OS scales window, event, and desktop geometry. The Cocoa platform plugin sets the scaling ratio as QWindow::devicePixelRatio() or QScreen::devicePixelRatio(), as well as on the backing store.

For QtWidgets, QPainter picks up devicePixelRatio() from the backing store and interprets it as a scaling ratio.

However, in OpenGL pixels are always device pixels. For example, geometry passed to glViewport() needs to be scaled by devicePixelRatio().

The specified font sizes (in points or pixels) do not change and strings retain their relative size compared to the rest of the UI. Fonts are scaled as a part of painting, so that a size 12 font effectively becomes a size 24 font with 2x scaling, regardless of whether it is specified in points or in pixels. The px unit is interpreted as device independent pixels to ensure that fonts do not appear smaller on a high DPI display.

You can select one high DPI device as a reference device and calculate a scaling ratio for adjusting image and font sizes and margins to the actual screen size.

The following code snippet uses reference values for DPI, height, and width from the Nexus 5 Android device, the actual screen size returned by the QRect class, and the logical DPI value of the

screen returned by the qApp global pointer to calculate a scaling ratio for image sizes and margins (m_ratio) and another for font sizes (m_ratioFont):

qreal refDpi = 216.; qreal refHeight = 1776.; qreal refWidth = 1080.; QRect rect = QGuiApplication::primaryScreen()->geometry(); qreal height = qMax(rect.width(), rect.height()); qreal width = qMin(rect.width(), rect.height()); qreal dpi = QGuiApplication::primaryScreen()->logicalDotsPerInch(); m_ratio = qMin(height/refHeight, width/refWidth); m_ratioFont = qMin(height*refDpi/(dpi*refHeight), width*refDpi/(dpi*refWidth));

For a reasonable scaling ratio, the height and width values must be set according to the default orientation of the reference device, which in this case is the portrait orientation.

The following code snippet sets the font scaling ratio to 1 if it would be less than one and thus cause the font sizes to become too small:

int tempTimeColumnWidth = 600; int tempTrackHeaderWidth = 270; if (m_ratioFont < 1.) { m_ratioFont = 1;

You should experiment with the target devices to find edge cases that require additional calculations. Some screens might just be too short or narrow to fit all the planned content and thus require their own layout. For example, you might need to hide or replace some content on screens with atypical aspect ratios, such as 1:1.

The scaling ratio can be applied to all sizes in a QQmlPropertyMap to scale images, fonts, and margins:

m_sizes = new QQmlPropertyMap(this); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("trackHeaderHeight"), QVariant(applyRatio(270))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("trackHeaderWidth"), QVariant(applyRatio(tempTrackHeaderWidth))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("timeColumnWidth"), QVariant(applyRatio(tempTimeColumnWidth))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("conferenceHeaderHeight"), QVariant(applyRatio(158))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("dayWidth"), QVariant(applyRatio(150))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("favoriteImageHeight"), QVariant(applyRatio(76))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("favoriteImageWidth"), QVariant(applyRatio(80))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("titleHeight"), QVariant(applyRatio(60))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("backHeight"), QVariant(applyRatio(74))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("backWidth"), QVariant(applyRatio(42))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("logoHeight"), QVariant(applyRatio(100))); m_sizes->insert(QLatin1String("logoWidth"), QVariant(applyRatio(286))); m_fonts = new QQmlPropertyMap(this); m_fonts->insert(QLatin1String("six_pt"), QVariant(applyFontRatio(9))); m_fonts->insert(QLatin1String("seven_pt"), QVariant(applyFontRatio(10))); m_fonts->insert(QLatin1String("eight_pt"), QVariant(applyFontRatio(12))); m_fonts->insert(QLatin1String("ten_pt"), QVariant(applyFontRatio(14))); m_fonts->insert(QLatin1String("twelve_pt"), QVariant(applyFontRatio(16))); m_margins = new QQmlPropertyMap(this); m_margins->insert(QLatin1String("five"), QVariant(applyRatio(5))); m_margins->insert(QLatin1String("seven"), QVariant(applyRatio(7))); m_margins->insert(QLatin1String("ten"), QVariant(applyRatio(10))); m_margins->insert(QLatin1String("fifteen"), QVariant(applyRatio(15))); m_margins->insert(QLatin1String("twenty"), QVariant(applyRatio(20))); m_margins->insert(QLatin1String("thirty"), QVariant(applyRatio(30)));

The functions in the following code snippet apply the scaling ratio to fonts, images, and margins:

int Theme::applyFontRatio(const int value) { return int(value * m_ratioFont); } int Theme::applyRatio(const int value) { return qMax(2, int(value * m_ratio)); }

This technique gives you reasonable results when the screen sizes of the target devices do not differ too much. If the differences are huge, consider creating several different layouts with different reference values.

You can use the QQmlFileSelector to apply a QFileSelector to QML file loading. This enables you to load alternative resources depending on the

platform on which the application is run. For example, you can use the +android file selector to load different image files when run on Android devices.

You can use file selectors together with singleton objects to access a single instance of an object on a particular platform.

File selectors are static and enforce a file structure where platform-specific files are stored in subfolders named after the platform. If you need a more dynamic solution for loading parts of your UI on demand, you can use a Loader.

The target platforms might automate the loading of alternative resources for different display densities in various ways. On Android and iOS, the @2x filename suffix is used to indicate high DPI versions of images.

The Image QML type and the QIcon class automatically load @2x versions of images and icons if they are provided. The QImage and QPixmap classes automatically set the devicePixelRatio of @2x versions of images to 2, but you need to add

code to actually use the @2x versions:

if ( QGuiApplication::primaryScreen()->devicePixelRatio() >= 2 ) { imageVariant = "@2x"; } else { imageVariant = ""; }

Android defines generalized screen sizes (small, normal, large, xlarge) and densities (ldpi, mdpi, hdpi, xhdpi, xxhdpi, and xxxhdpi) for which you can create alternative resources. Android detects the current device configuration at runtime and loads the appropriate resources for your application. However, beginning with Android 3.2 (API level 13), these size groups are deprecated in favor of a new technique for managing screen sizes based on the available screen width.

A Loader can load a QML file (using the source property) or a Component object (using the sourceComponent property). It is

useful for delaying the creation of a component until it is required. For example, when a component should be created on demand, or when a component should not be created unnecessarily for performance reasons.

You can also use loaders to react to situations where parts of your UI are not needed on a particular platform, because the platform does not support some functionality. Instead of displaying a view that is not needed on the device the application is running on, you can determine that the view is hidden and use loaders to display something else in its place.

The Screen.orientation attached property contains the current orientation of the screen, from the accelerometer (if available). On a desktop computer, this value typically does not change.

If primaryOrientation follows orientation, it means that the screen automatically rotates all content that is displayed, depending on how you hold the device. If

orientation changes even though primaryOrientation does not change, the device might not rotate its own display. In that case, you may need to use Item.rotation or Item.transform to rotate your content.

Application top-level page definitions and reusable component definitions should use one QML layout definition for the layout structure. This single definition should include the layout design for separate device orientations and aspect ratios. The reason for this is that performance during an orientation switch is critical, and it is therefore a good idea to ensure that all of the components needed by both orientations are loaded when the orientation changes.

On the contrary, you should perform thorough tests if you choose to use a Loader to load additional QML that is needed in separate orientations, as this will affect the performance of the orientation change.

In order to enable layout animations between the orientations, the anchor definitions must reside within the same containing component. Therefore the structure of a page or a component should consist of a common set of child components, a common set of anchor definitions, and a collection of states (defined in a StateGroup) representing the different aspect ratios supported by the component.

If a component contained within a page needs to be hosted in numerous different form factor definitions, then the layout states of the view should depend on the aspect ratio of the page (its immediate container). Similarly, different instances of a component might be situated within numerous different containers in a UI, and so its layout states should be determined by the aspect ratio of its parent. The conclusion is that layout states should always follow the aspect ratio of the direct container (not the "orientation" of the current device screen).

Within each layout State, you should define the relationships between items using native QML layout definitions. See below for more information. During transitions between the states (triggered by the top level orientation change), in the case of anchor layouts, AnchorAnimation elements can be used to control the transitions. In some cases, you can also use a NumberAnimation on e.g. the width of an item. Remember to avoid complex JavaScript calculations during each frame of animation. Using simple anchor definitions and anchor animations can help with this in the majority of cases.

There are a few additional cases to consider: