In GUI programming, when we change one widget, we often want another widget to be notified. More generally, we want objects of any kind to be able to communicate with one another. For example, if a user clicks a Close button, we probably want the window's close() function to be called.

Other toolkits achieve this kind of communication using callbacks. A callback is a pointer to a function, so if you want a processing function to notify you about some event you pass a pointer to another function (the callback) to the processing function. The processing function then calls the callback when appropriate. While successful frameworks using this method do exist, callbacks can be unintuitive and may suffer from problems in ensuring the type-correctness of callback arguments.

In Qt, we have an alternative to the callback technique: We use signals and slots. A signal is emitted when a particular event occurs. Qt's widgets have many predefined signals, but we can always subclass widgets to add our own signals to them. A slot is a function that is called in response to a particular signal. Qt's widgets have many pre-defined slots, but it is common practice to subclass widgets and add your own slots so that you can handle the signals that you are interested in.

The signals and slots mechanism is type safe: The signature of a signal must match the signature of the receiving slot. (In fact a slot may have a shorter signature than the signal it receives because it can ignore extra arguments.) Since the signatures are compatible, the compiler can help us detect type mismatches when using the function pointer-based syntax. The string-based SIGNAL and SLOT syntax will detect type mismatches at runtime. Signals and slots are loosely coupled: A class which emits a signal neither knows nor cares which slots receive the signal. Qt's signals and slots mechanism ensures that if you connect a signal to a slot, the slot will be called with the signal's parameters at the right time. Signals and slots can take any number of arguments of any type. They are completely type safe.

All classes that inherit from QObject or one of its subclasses (e.g., QWidget) can contain signals and slots. Signals are emitted by objects when they change their state in a way that may be interesting to other objects. This is all the object does to communicate. It does not know or care whether anything is receiving the signals it emits. This is true information encapsulation, and ensures that the object can be used as a software component.

Slots can be used for receiving signals, but they are also normal member functions. Just as an object does not know if anything receives its signals, a slot does not know if it has any signals connected to it. This ensures that truly independent components can be created with Qt.

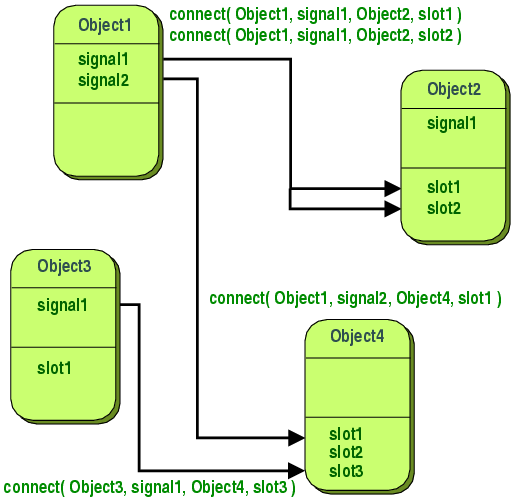

You can connect as many signals as you want to a single slot, and a signal can be connected to as many slots as you need. It is even possible to connect a signal directly to another signal. (This will emit the second signal immediately whenever the first is emitted.)

Together, signals and slots make up a powerful component programming mechanism.

Signals are emitted by an object when its internal state has changed in some way that might be interesting to the object's client or owner. Signals are public access functions and can be emitted from anywhere, but we recommend to only emit them from the class that defines the signal and its subclasses.

When a signal is emitted, the slots connected to it are usually executed immediately, just like a normal function call. When this happens, the signals and slots mechanism is totally independent of any GUI event loop.

Execution of the code following the emit statement will occur once all slots have returned. The situation is slightly different when using queued

connections; in such a case, the code following the emit keyword will continue immediately, and the slots will be executed later.

If several slots are connected to one signal, the slots will be executed one after the other, in the order they have been connected, when the signal is emitted.

Signals are automatically generated by the moc and must not be implemented in the .cpp file.

A note about arguments: Our experience shows that signals and slots are more reusable if they do not use special types. If QScrollBar::valueChanged() were to use a special type such as the hypothetical QScrollBar::Range, it could only be connected to slots designed specifically for QScrollBar. Connecting different input widgets together would be impossible.

A slot is called when a signal connected to it is emitted. Slots are normal C++ functions and can be called normally; their only special feature is that signals can be connected to them.

Since slots are normal member functions, they follow the normal C++ rules when called directly. However, as slots, they can be invoked by any component, regardless of its access level, via a signal-slot connection. This means that a signal emitted from an instance of an arbitrary class can cause a private slot to be invoked in an instance of an unrelated class.

You can also define slots to be virtual, which we have found quite useful in practice.

Compared to callbacks, signals and slots are slightly slower because of the increased flexibility they provide, although the difference for real applications is insignificant. In general, emitting a signal that is connected

to some slots, is approximately ten times slower than calling the receivers directly, with non-virtual function calls. This is the overhead required to locate the connection object, to safely iterate over all connections (i.e.

checking that subsequent receivers have not been destroyed during the emission), and to marshall any parameters in a generic fashion. While ten non-virtual function calls may sound like a lot, it's much less overhead than any

new or delete operation, for example. As soon as you perform a string, vector or list operation that behind the scene requires new or

delete, the signals and slots overhead is only responsible for a very small proportion of the complete function call costs. The same is true whenever you do a system call in a slot; or indirectly

call more than ten functions. The simplicity and flexibility of the signals and slots mechanism is well worth the overhead, which your users won't even notice.

Note that other libraries that define variables called signals or slots may cause compiler warnings and errors when compiled alongside a Qt-based application. To solve

this problem, #undef the offending preprocessor symbol.

A minimal C++ class declaration might read:

class Counter { public: Counter() { m_value = 0; } int value() const { return m_value; } void setValue(int value); private: int m_value; };

A small QObject-based class might read:

#include <QObject> class Counter : public QObject { Q_OBJECT // Note. The Q_OBJECT macro starts a private section. // To declare public members, use the 'public:' access modifier. public: Counter() { m_value = 0; } int value() const { return m_value; } public slots: void setValue(int value); signals: void valueChanged(int newValue); private: int m_value; };

The QObject-based version has the same internal state, and provides public methods to access the state, but in addition it has support for component programming using signals and slots. This

class can tell the outside world that its state has changed by emitting a signal, valueChanged(), and it has a slot which other objects can send signals to.

All classes that contain signals or slots must mention Q_OBJECT at the top of their declaration. They must also derive (directly or indirectly) from QObject.

Slots are implemented by the application programmer. Here is a possible implementation of the Counter::setValue() slot:

void Counter::setValue(int value) { if (value != m_value) { m_value = value; emit valueChanged(value); } }

The emit line emits the signal valueChanged() from the object, with the new value as argument.

In the following code snippet, we create two Counter objects and connect the first object's valueChanged() signal to the second object's setValue() slot using QObject::connect():

Counter a, b; QObject::connect(&a, &Counter::valueChanged, &b, &Counter::setValue); a.setValue(12); // a.value() == 12, b.value() == 12 b.setValue(48); // a.value() == 12, b.value() == 48

Calling a.setValue(12) makes a emit a valueChanged(12) signal, which b will receive in its setValue() slot, i.e. b.setValue(12) is called. Then b emits the same valueChanged() signal, but since no slot has been connected

to b's valueChanged() signal, the signal is ignored.

Note that the setValue() function sets the value and emits the signal only if value != m_value. This prevents infinite looping in the case of cyclic connections (e.g.,

if b.valueChanged() were connected to a.setValue()).

By default, for every connection you make, a signal is emitted; two signals are emitted for duplicate connections. You can break all of these connections with a single disconnect()

call. If you pass the Qt::UniqueConnection type, the connection will only be made if it is not a duplicate. If there is already a duplicate (exact same signal

to the exact same slot on the same objects), the connection will fail and connect will return false.

This example illustrates that objects can work together without needing to know any information about each other. To enable this, the objects only need to be connected together, and this can be achieved with some simple QObject::connect() function calls, or with uic's automatic connections feature.

The following is an example of the header of a simple widget class without member functions. The purpose is to show how you can utilize signals and slots in your own applications.

#ifndef LCDNUMBER_H #define LCDNUMBER_H #include <QFrame> class LcdNumber : public QFrame { Q_OBJECT

LcdNumber inherits QObject, which has most of the signal-slot knowledge, via QFrame and QWidget. It is

somewhat similar to the built-in QLCDNumber widget.

The Q_OBJECT macro is expanded by the preprocessor to declare several member functions that are implemented by the moc; if you get compiler errors along the

lines of "undefined reference to vtable for LcdNumber", you have probably forgotten to run the moc or to include the moc output in the link command.

public: LcdNumber(QWidget *parent = nullptr); signals: void overflow();

After the class constructor and public members, we declare the class signals. The LcdNumber class emits a signal, overflow(), when it is asked to show an impossible value.

If you don't care about overflow, or you know that overflow cannot occur, you can ignore the overflow() signal, i.e. don't connect it to any slot.

If on the other hand you want to call two different error functions when the number overflows, simply connect the signal to two different slots. Qt will call both (in the order they were connected).

public slots: void display(int num); void display(double num); void display(const QString &str); void setHexMode(); void setDecMode(); void setOctMode(); void setBinMode(); void setSmallDecimalPoint(bool point); }; #endif

A slot is a receiving function used to get information about state changes in other widgets. LcdNumber uses it, as the code above indicates, to set the displayed number. Since display() is part of the class's interface with the rest of the program, the slot is public.

Several of the example programs connect the valueChanged() signal of a QScrollBar to the display() slot, so

the LCD number continuously shows the value of the scroll bar.

Note that display() is overloaded; Qt will select the appropriate version when you connect a signal to the slot. With callbacks, you'd have to find five different names and keep track of the types

yourself.

The signatures of signals and slots may contain arguments, and the arguments can have default values. Consider QObject::destroyed():

void destroyed(QObject* = nullptr);

When a QObject is deleted, it emits this QObject::destroyed() signal. We want to catch this signal, wherever we might have a dangling reference to the deleted QObject, so we can clean it up. A suitable slot signature might be:

void objectDestroyed(QObject* obj = nullptr);

To connect the signal to the slot, we use QObject::connect(). There are several ways to connect signal and slots. The first is to use function pointers:

connect(sender, &QObject::destroyed, this, &MyObject::objectDestroyed);

There are several advantages to using QObject::connect() with function pointers. First, it allows the compiler to check that the signal's arguments are compatible with the slot's arguments. Arguments can also be implicitly converted by the compiler, if needed.

You can also connect to functors or C++11 lambdas:

connect(sender, &QObject::destroyed, this, [=](){ this->m_objects.remove(sender); });

In both these cases, we provide this as context in the call to connect(). The context object provides information about in which thread the receiver should be executed. This is important, as providing the context ensures that the receiver is executed in the context thread.

The lambda will be disconnected when the sender or context is destroyed. You should take care that any objects used inside the functor are still alive when the signal is emitted.

The other way to connect a signal to a slot is to use QObject::connect() and the SIGNAL and SLOT macros. The rule about whether

to include arguments or not in the SIGNAL() and SLOT() macros, if the arguments have default values, is that the signature passed to the SIGNAL() macro must not have fewer arguments than the signature passed to the SLOT() macro.

All of these would work:

connect(sender, SIGNAL(destroyed(QObject*)), this, SLOT(objectDestroyed(Qbject*))); connect(sender, SIGNAL(destroyed(QObject*)), this, SLOT(objectDestroyed())); connect(sender, SIGNAL(destroyed()), this, SLOT(objectDestroyed()));

But this one won't work:

connect(sender, SIGNAL(destroyed()), this, SLOT(objectDestroyed(QObject*)));

...because the slot will be expecting a QObject that the signal will not send. This connection will report a runtime error.

Note that signal and slot arguments are not checked by the compiler when using this QObject::connect() overload.

For cases where you may require information on the sender of the signal, Qt provides the QObject::sender() function, which returns a pointer to the object that sent the signal.

Lambda expressions are a convenient way to pass custom arguments to a slot:

connect(action, &QAction::triggered, engine, [=]() { engine->processAction(action->text()); });

It is possible to use Qt with a 3rd party signal/slot mechanism. You can even use both mechanisms in the same project. To do that, write the following into your CMake project file:

target_compile_definitions(my_app PRIVATE QT_NO_KEYWORDS)

In a qmake project (.pro) file, you need to write:

CONFIG += no_keywords

It tells Qt not to define the moc keywords signals, slots, and emit, because these names will be used by a 3rd party library, e.g. Boost.

Then to continue using Qt signals and slots with the no_keywords flag, simply replace all uses of the Qt moc keywords in your sources with the corresponding Qt macros Q_SIGNALS (or Q_SIGNAL), Q_SLOTS (or Q_SLOT), and Q_EMIT.

The public API of Qt-based libraries should use the keywords Q_SIGNALS and Q_SLOTS instead of signals and slots.

Otherwise it is hard to use such a library in a project that defines QT_NO_KEYWORDS.

To enforce this restriction, the library creator may set the preprocessor define QT_NO_SIGNALS_SLOTS_KEYWORDS when building the library.

This define excludes signals and slots without affecting whether other Qt-specific keywords can be used in the library implementation.

See also QLCDNumber, QObject::connect(), Meta-Object System, and Qt's Property System.