Threads are about doing things in parallel, just like processes. So how do threads differ from processes? While you are making calculations on a spreadsheet, there may also be a media player running on the same desktop playing your favorite song. Here is an example of two processes working in parallel: one running the spreadsheet program; one running a media player. Multitasking is a well known term for this. A closer look at the media player reveals that there are again things going on in parallel within one single process. While the media player is sending music to the audio driver, the user interface with all its bells and whistles is being constantly updated. This is what threads are for – concurrency within one single process.

So how is concurrency implemented? Parallel work on single core CPUs is an illusion which is somewhat similar to the illusion of moving images in cinema. For processes, the illusion is produced by interrupting the processor's work on one process after a very short time. Then the processor moves on to the next process. In order to switch between processes, the current program counter is saved and the next processor's program counter is loaded. This is not sufficient because the same needs to be done with registers and certain architecture and OS specific data.

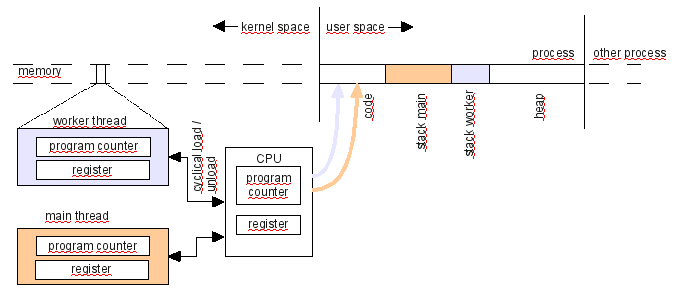

Just as one CPU can power two or more processes, it is also possible to let the CPU run on two different code segments of one single process. When a process starts, it always executes one code segment and therefore the process is said to have one thread. However, the program may decide to start a second thread. Then, two different code sequences are processed simultaneously inside one process. Concurrency is achieved on single core CPUs by repeatedly saving program counters and registers then loading the next thread's program counters and registers. No cooperation from the program is required to cycle between the active threads. A thread may be in any state when the switch to the next thread occurs.

The current trend in CPU design is to have several cores. A typical single-threaded application can make use of only one core. However, a program with multiple threads can be assigned to multiple cores, making things happen in a truly concurrent way. As a result, distributing work to more than one thread can make a program run much faster on multicore CPUs because additional cores can be used.

As mentioned, each program has one thread when it is started. This thread is called the "main thread" (also known as the "GUI thread" in Qt applications). The Qt GUI must run in this thread. All widgets and several related classes, for example QPixmap, don't work in secondary threads. A secondary thread is commonly referred to as a "worker thread" because it is used to offload processing work from the main thread.

Each thread has its own stack, which means each thread has its own call history and local variables. Unlike processes, threads share the same address space. The following diagram shows how the building blocks of threads are located in memory. Program counter and registers of inactive threads are typically kept in kernel space. There is a shared copy of the code and a separate stack for each thread.

If two threads have a pointer to the same object, it is possible that both threads will access that object at the same time and this can potentially destroy the object's integrity. It's easy to imagine the many things that can go wrong when two methods of the same object are executed simultaneously.

Sometimes it is necessary to access one object from different threads; for example, when objects living in different threads need to communicate. Since threads use the same address space, it is easier and faster for threads to exchange data than it is for processes. Data does not have to be serialized and copied. Passing pointers is possible, but there must be a strict coordination of what thread touches which object. Simultaneous execution of operations on one object must be prevented. There are several ways of achieving this and some of them are described below.

So what can be done safely? All objects created in a thread can be used safely within that thread provided that other threads don't have references to them and objects don't have implicit coupling with other threads. Such implicit coupling may happen when data is shared between instances as with static members, singletons or global data. Familiarize yourself with the concept of thread safe and reentrant classes and functions.

There are basically two use cases for threads:

Developers need to be very careful with threads. It is easy to start other threads, but very hard to ensure that all shared data remains consistent. Problems are often hard to find because they may only show up once in a while or only on specific hardware configurations. Before creating threads to solve certain problems, possible alternatives should be considered.

| Alternative | Comment |

|---|---|

| QEventLoop::processEvents() | Calling QEventLoop::processEvents() repeatedly during a time-consuming calculation prevents GUI blocking. However, this solution doesn't scale well because the call to processEvents() may occur too often, or not often enough, depending on hardware. |

| QTimer | Background processing can sometimes be done conveniently using a timer to schedule execution of a slot at some point in the future. A timer with an interval of 0 will time out as soon as there are no more events to process. |

| QSocketNotifier QNetworkAccessManager QIODevice::readyRead() | This is an alternative to having one or multiple threads, each with a blocking read on a slow network connection. As long as the calculation in response to a chunk of network data can be executed quickly, this reactive design is better than synchronous waiting in threads. Reactive design is less error prone and energy efficient than threading. In many cases there are also performance benefits. |

In general, it is recommended to only use safe and tested paths and to avoid introducing ad-hoc threading concepts. The QtConcurrent module provides an easy interface for distributing work to all of the processor's cores. The threading code is completely hidden in the QtConcurrent framework, so you don't have to take care of the details. However, QtConcurrent can't be used when communication with the running thread is needed, and it shouldn't be used to handle blocking operations.

See the Multithreading Technologies in Qt page for an introduction to the different approaches to multithreading to Qt, and for guidelines on how to choose among them.

The following sections describe how QObjects interact with threads, how programs can safely access data from multiple threads, and how asynchronous execution produces results without blocking a thread.

As mentioned above, developers must always be careful when calling objects' methods from other threads. Thread affinity does not change this situation. Qt documentation marks several methods as thread-safe. postEvent() is a noteworthy example. A thread-safe method may be called from different threads simultaneously.

In cases where there is usually no concurrent access to methods, calling non-thread-safe methods of objects in other threads may work thousands of times before a concurrent access occurs, causing unexpected behavior. Writing test code does not entirely ensure thread correctness, but it is still important. On Linux, Valgrind and Helgrind can help detect threading errors.

When writing a multithread application, extra care must be taken to avoid data corruption. See Synchronizing Threads for a discussion on how to use threads safely.

One way to obtain a worker thread's result is by waiting for the thread to terminate. In many cases, however, a blocking wait isn't acceptable. The alternative to a blocking wait are asynchronous result deliveries with either posted events or queued signals and slots. This generates a certain overhead because an operation's result does not appear on the next source line, but in a slot located somewhere else in the source file. Qt developers are used to working with this kind of asynchronous behavior because it is much similar to the kind of event-driven programming used in GUI applications.

Qt comes with several examples for using threads. See the class references for QThread and QThreadPool for simple examples. See the Threading and Concurrent Programming Examples page for more advanced ones.

Threading is a very complicated subject. Qt offers more classes for threading than we have presented in this tutorial. The following materials can help you go into the subject in more depth: